|

It was during these prolonged convalescences spent in the rural landscapes of Riudoms and cared for by parents who had already lost two children, that many shapes from Nature must have become imprinted on the mind of the boy to be used later in his architecture.

We know that his father was a pioneer of what we now know as naturist practices and not just with diet, but also with regard to healing, a follower of Abbot Kneipp in the benefits derived from hydrotherapy and walking barefoot on the grass. The mother, always on top of the diet of that sickly child, continued to receive letters almost daily until he was more than twenty years old in which he informed her of his state of health and his occupations.

The women that surrounded him in his family – mother, sister and niece – looked after him at the table. And others not blood-related, also. The monks that attended to the upkeep of the Güell Park chalet where he lived between 1906 and 1925 told that boiled green beans with potatoes and an onion, all sprinkled with olive oil, and cabbage with potatoes which he covered in a light allioli (garlic mayonnaise), were his favourite dishes.

The three generations of the Alpiste family who supervised the work, the visits and the domestic arrangements of the architect from 1900 to 1926 are testament to the fact that Gaudi controlled everything to do with hopusekeeping, whether it was to do with the concave curvature that his bed must display, deciding whether the range in the kitchen should be wood-burning instead of using coal or which method was best for ensuring that vegetables retained the maximum amount of their vitamins when cooked. To achieve the latter, Gaudi made Mrs Alpiste roll up a kitchen cloth and tie it to one of the handles of the pot, then it had to be passed through the handle of the lid and tied to the opposite handle of the pot. Impeding the exit of steam in order to reduce cooking time was an elementary and early form of what would later be commercialised as a pressure cooker.

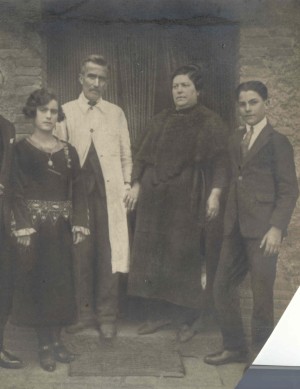

The guards, Jerónimo Alpiste and his wife Mª Eugenia García with their children Gregoria and Andrés.

|

A memory from those days could be the offer Gaudi made to the temple guards, Jeronimo Alpiste and his wife Mª Eugenia and the rest of the construction workers, letting them use the adjacent land to plant whatever they wanted. Vegetables and pulses were the chosen produce, with the addition of some fruit trees suggested by the architect who in the last years of his life liked to go himself in the mornings to collect figs and plums from the trees for his breakfast. In this respect, Gregoria and Andres, the children of the Alpiste family, would later tell their children that they used to go up to Gaudi’s study to watch his ritual of emptying out a yoghurt tub into a bowl, adding chopped fruit and, putting on gloves, mixin it all up with his hands. He then proceeded to eat it all with a spoon as if it were soup, before the amused gaze of the youngsters. |

The architect consumed a homemade product that was possibly the same as that which a few years later would be sold under the brand name Danone, today a world leader in dairy but in 1919 Isaac Carasso began to make it in Barcelona, underneath his house at Nº 1 Los Angeles Street, very close to Las Ramblas. Carasso worked manually at his modest business although his methods were sophisticated, following the guidelines of the Nobel Prizewinner for Medicine, Elias Metchnikoff, of the Pasteur Institute. Francesc Gaudi’s ideas about how to treat the organism crystallised with his son’s maturity when, using an affectionate tone not very common in his dialogue with adults, assured his little yoghurt and fruit-mixing spectators: I do it to save work for my stomach.

In the centre, 7th from the left, Isaac Carasso poses under his house at Nº1 Los Angeles Street in Barcelona, where the first commercial yoghurt of the world was born.

|

As in other parts of his life, here the architect was a pioneer, not just because around 1920 the yoghurt was an almost unknown foodstuff in Spain, but also because the combination of fruit he added to it was not commercialised until eleven years after his death. Gaudi tended to buy a half dozen tubs that he would leave lined up on the table he used as both desk and dining table and, through not refrigerating them, the fermentation caused the surface to become covered in a layer of minute green fungi that he would remove before commencing his manual mixing. This provoked some of the construction workers and others who were against the figure of the architect, to spread the rumour that he used to eat the fungi from yoghurts that they thought to be hallucinogenic, as well as other toxic mushrooms, and that was why he planned architectural works in strange bulbous and twisted shapes. The mushroom theory rested upon the weak premise that no-one else had ever thought of adorning the portal of a building with this vegetables, as he did in the Casa Calvet. |

What his detractors didn’t know is that the idea of placing mushrooms on the facade came from the fact that Mr Calvet loved to eat them, as well as being an expert connoisseur, he used to pick them in the forests and often sent them to Gaudi in a little basket. So making mushrooms a part of the decor held no great mystery, in the same way that the architect included reels of thread within the portal as homage to the product that Calvet manufactured, he also included the mushrooms as a nod to their friendship.

The restaurant installed within the Casa Calvet for many years tended to receive patrons as famous as Harrison Ford, Pelé, John Malkovich or Woody Allen whenever they visited Barcelona, and the metre high blue-dyed tile that decorated the residents entrance owes its design to the one in the dining room of Pepeta Moreu Fornells, the only woman – that is known of, at least – whose hand in marriage was requested by Gaudi. For ten years the architect went to the Moreu-Fornells family home in Mataró on many Sundays accompanied by his niece Rosita to eat in the company of Pepeta, her brother Josep Mª and their parents, where a layer of blue mosaic of the same features greeted the guest.

The manuscripts left by Pepeta’s brother tell us that as a child he was fascinated with the figure of the architect, up to the point of deciding to begin the same career. In the eyes of the little Josep Mª, Gaudi left the impression of a man with interesting opinions, who folded the serviette in an original manner, rubbed the bottle of wine with a cloth to facilitate the uncorking and ate noodles and when some of them would become entangled in his beard he would calmly remove them with a fork.

As well as the Calvet restaurant, it is interesting to note the number of buildings constructed by Gaudi that have ended up hosting an establishment that feeds his admirers. In Barcelona, as a student who collaborated with Josep Fontseré, author of the building, Gaudi undoubtedly designed the columns that can be seen in the basement of the old Terminus restaurant, today Tasca Vins, in front of the Francia station, as well as the Parque de la Ciudadela where the splendid railings bear his imprint, enclosing a number of venues with tables, drinks and bars. Can Pujades in Vallgorguina still has in its chapel the miniscule stained glass windows designed by Gaudi with motifs that he would later use in the Birth Facade, this exquisite piece of work can be viewed if those interested contact the management of the Carpier company, owner of the estate, a Catalan company that through marinating wild Norwegian salmon with olive oil and a special smoke has managed to ensure that products produced in a small village in the Montnegre mountain range attract restaurateurs and wholesalers from all over Europe.

Then comes the Casa Batlló, in which the rooms off its reception area are hired for banquets. The six-armed lamp-posts that he made for the Plaza Real illuminate a wide circle of bars and restaurants and the same happens in the interior part of the Güell park. The Capricho en Comillas, Cantabria, hosts a luxurious international restaurant. In Garraf, at Km 16 of the Barcelona to Sitges road, the little known Güell Cellars with its pagoda peaks provide a stone framework for the restaurant they advertise. In this quick stroll through Gaudinian venues dedicated to gastronomy we would also cite the Caballerizas Güell that host the Gaudi Cathedral, where the pavilion is as dandy as the railings guarded by the wrought iron dragon, make those who came up to the structure ask of the Professor Joan Bassegoda, Department director for 40 years: Are wedding banquets held here? To which he would sarcastically reply: Well look, no. But you are giving me an idea...

A table companion along these lines was someone who keeps a surprising anecdote about Gaudi and his malevolent streak. It refers to the benefactor who, as he often helped him with cash donations, considered he had the right to demand a present from the architect, something Very out of the ordinary, something that no-one has seen before. To Gaudi, the insistence of the gentleman seemed in very bad taste as a gift, so thought he, is one that is deserved but never demanded. However, the benefactor persisted and persisted with his request until one day, fed up with the man who continually asked for something original, that has never been seen before, sent Andrés, the son of one of the guards, to buy a black botijo (drinking jug) typical of Barcelona, and with a very delicate brace the architect entertained himself forming arabesques with perforations on the belly of the jug.

When it was finished, he sent it by hand via Andrés and the following morning the benefactor appeared very indignant, waving the botijo and saying: What you have given me is good for nothing. To which Gaudi replied: You didn’t tell me it had to be good for something. You repeated a thousand times that it had to be “original” and “something that had never been seen before”. Well you can be sure that no-one before you has seen something like that”.

From the era between 1880 and 1911 when both his personal and professional life blossomed, it is known that he spent years of fine dining in good restaurants and at the best burghers, aristocratic and ecclesiastical tables, without forgetting fine wine and a quality Habana, but at the end of his life he liked nothing more than to eat the dried fruit sent to him from his village in the Campo de Tarragona, an aroma from his childhood that accompanied him on his last journey towards the Sant Felipe Neri oratory on the day he received the impact from the route 30 streetcar, as a result of injuries from which he died three days later in the Santa Creu hospital. When his friends were handed the belongings and clothes that Gaudi was wearing that fateful day they confirmed that he was walking around Barcelona without money or documentation, on his travels throughout the capital he had nothing more than a copy of the gospels and a handful of nuts in his pockets.

|